As you might imagine, reading is a substantial part of my creative writing PhD. I’m reading primary and secondary sources, I’m reading fiction, and I’m always on the lookout for historical novels about women revolutionaries, Russian specifically. In historical fiction about Russia centered on women, most of what you’ll find are novels about bourgeoisie gentry ladies and how the revolution disenfranchised them, rather than focusing on women’s empowerment from participating in it. Usually, it’s a love story where the revolution is a backdrop which happens to wealthy women, against them (think The Jewel of St. Petersburg by Kate Furnivall and Emily (The Kirov Saga #3) by Cynthia Harrod-Eagels). Now and then revolutionary women get the fictional spotlight – more often than the historical one: To Kill a Tsar by Andrew Williams draws heavily from the memoirs of revolutionary women of the 1870s & ’80s which I’ll be quoting from later on, and while female revolutionaries are not the sole focus they are in the forefront and realistic (although the main fictional woman is still from a bourgeoisie background); Sashenka by Simon Sebag Montefiore contextualizes radicalism in general and female radicalism specifically as a very small part of the greater Russian 20th century narrative but nevertheless presents us with a woman passionate about the cause (although she’s still from a bourgeoisie background).

Then, there’s Saturn’s Daughters by Jim Pinnells.

I had such high hopes for this novel, given that it purports to be solely about the women of Narodnaya Volya, The People’s Will, the terrorist organization I have mentioned in previous posts (and will be discussing later this month at the FiLiA feminism conference in London). This particular branch of the revolutionary movement comes about a decade before that covered in my novel, but it is always a joy to find someone giving these women the credit they’re due, particularly in the more accessible format of fiction.

Except not in this case.

Do not be mistaken: this novel is a masturbatory fantasy masquerading as a portrayal of women’s role in a (semi-) organized terrorist network. It was gratuity disguised as research. It read like an excuse to write about a hot, often naked woman for several hundred pages without actually providing any political context even though she’s a revolutionary – or supposed to be. Evgenya’s aims and desires are muddled, and her function within the movement equally so. It is explicitly stated at one point that it would be useful having a woman as attractive as Evgenya in the movement, since the other women aren’t very attractive. Is that…important for a revolutionary? Never a mention of the importance of the men’s looks, incidentally.

Evgenya’s main skill appears to be taking her clothes off. In fact, almost her entire focus is physically or sexually based. Her early scenes – where she pursues socialism as a means to the cousin she’s in love with – revolve solely around her desperation to have sex. Once involved in the movement (given no assignments and providing no contribution), she takes to stripping at the least provocation and taking many of her male comrades to bed. For the sake of “art” and “free love”, obviously. But Pinnells’ understanding of the free love seems informed more by 1960’s themes of sexual liberation rather than 1860’s themes of marriage laws and gender relations. She even sleeps with a few female comrades, and early on this is done for the amusement of the men in her circle. Riiiiiight…

Out of curiosity, I did a little digging and found an interview with Pinnells from Soviet Roulette in July 2013. Apparently Pinnells started this novel as a college grad in the 1960s (see the aforementioned misunderstanding of the term “free love”) who “knew very little about revolution and even less about women”, returned to it in middle age having “learned a lot more about revolution and a shade more about women”, and finished it in his late sixties, with the addendum that he’d “had a good look at terrorism from the practical, preventative side and…thought a great deal about female psychology – which is not to say that I’d understood women. Far from it.”

THAT much was obvious.

I won’t waste time on the flat, bland prose or the dialogue which fluctuated between vague, forgettable, or completely ridiculous. Nor on the less-than-gripping plot, perhaps because I had to stop every few pages (or every few paragraphs) and either roll my eyes or cringe because, as I say, it was so gratuitous. Everything revolved around writing Evgenya in the nude, whether posing as a model, boxing in Moscow, or simply walking around au naturel. Not to mention the vacuous invented characters, particularly Evgenya and her lover/cousin Vitya who have no personality outside of each other, and whose plots revolve around each other more than any political ideology. All of this put me off as a reader and as an author, but as a researcher I pressed on, and came away with many more questions about the role and ethics of historical fiction and research, and motivations of authors of historical fiction, and publication industry generally.

Aside from my issues with his plot and his style, I take issue with his method of research; or at least the way he manipulated or ignored the facts to serve an unknown authorial agenda.

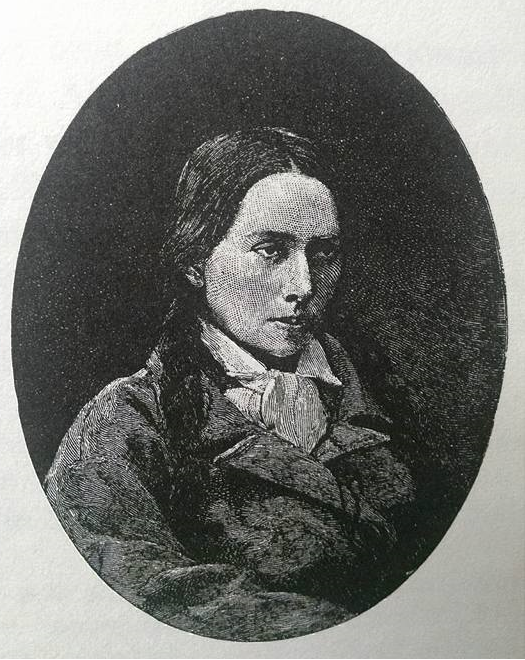

Specifically: it does a HUGE disservice to Sofia Perovskaya. Never, in any memoir or academic text I’ve read, have I found any recollections of her that made her sound as personally cold, calculating, manipulative, aloof, vindictive, or unhinged as this novel made her out to be. From accounts of people who knew her, she was very much the opposite. Yes, as a revolutionary and terrorist she needed all of those traits professionally, in some degree, to achieve her ends. But the descriptions of her character and her relationships with other revolutionaries in the novel struck me as unlikely from the start, and became more and more inaccurate as I read. And now, working on the presentation about female friendship in the underground for the conference, as I trawl again through first-hand accounts from those who knew her, I can’t see anything at all of the woman Pinnells described. (Plus, his obsession with her looks is A) irrelevant, B) exaggerated [he makes a point several times of referring to her as unattractive and saying she’d never get a man to love her], and C) brings me back to my original complaint about literal masculine wankery.)

In the novel, her comrades seem resentful of her authority even when they’ve asked for her guidance. They bemoan her decisions and her strictures on their personal lives. They complain about her behind her back and blame her for each setback. It leaves the reader in doubt as to why anyone would follow her at all or let the movement build up around her. From a narrative standpoint, it makes no sense – because from a historical standpoint it’s inaccurate. The women especially despise her for being cold and manipulative, for putting the movement ahead of all personal relationships.

Yet we know those revolutionary strictures about personal lives and relationships were never adhered to, or not by a large proportion of revolutionaries in the decades leading up to 1917. Within Narodnaya Volya, for all the grand talk about the primacy of revolution in their minds and hearts, we see examples again and again of comrades whose relationships transcend the physical and become romantic, leading to underground marriages and even children. Olga Liubatovich, Gesia Gelfman, Anna Yakimova: all were involved with men in the movement, all had children with their partners. Liubatovich crossed countries to get her lover out of prison rather than leave the task to another comrade.

Sofia Perovskaya, for all her leadership qualities, was not immune to romantic entanglements. As I have outlined in an earlier post (January 20, 2017), her relationship with Andrei Zhelyabov, despite his already being married, was one of intellectual and spiritual equals. And the feelings between them were mutual. We know this from the memoirs of those who were close to them, men and women. And yet Pinnells keeps them separate for most of the novel, brings them together long enough for Perovskaya to ask Vitya if he is surprised at her sexual relationship with Zhelyabov given how unattractive she is (“ugly” is the word he used in a HuffPost blog post titled “Women and Terror” from July 2013), and then to have Zhelyabov tire of her, abandon her, and leave her weak and pining for contact…and thus yearning for a sexual relationship with heroine Evgenya. With plenty of scenes describing the women’s sexual exploits in language both euphemistic and unnecessary. Not to mention, out of character. Evgenya’s lesbian activity has, thus far, been strictly for men’s entertainment; her expressed and narrated desires have, up to now, always been for men. Perovskaya, in the novel, appraises Evgenya constantly for her physical attributes, but always for what they can contribute to the movement. Until they become a viable option for some reason. Historical Perovskaya appears, as far as the primary source material can show us, heterosexual.

All of this led me to question Pinnells’ sources. Many historical novels come with author’s notes where they clarify what is fictional, what is real, their methodology, and the sources they utilized. Most, actually. Reputable novels, definitely. Pinnells hasn’t provided any such information. The closest I came to sources were: a biography of Zhelyabov called Red Prelude from the 40’s (which I have ordered and am looking forward to reading for my project as well as enlightenment on this text), “a stack of history books and biographies” (unnamed), and “from everything that ever happened to [him] really”. (From an interview with Frost Magazine, August 2013.) The aforementioned interview in Soviet Roulette simply gives us “half a century of reading, asking and discussing with practitioners on both sides of the terrorist fence” as his research.

Interestingly, the chapters of the fictional novel are interspersed with excerpts from the memoir of an anonymous revolutionary of the period known only as MF, which Pinnells attributes to Mikhail Frolenko. The excerpts follow along with the plot, and it gives us an insight into where Pinnells drew his inspiration in several places, for characters and for events. I noticed one line where MF blames Perovskaya for a mission’s failure, saying things were done solely to keep her from losing an argument, but aside from that, there’s nothing of the disdain shown for her by the radicals in Pinnells’ work. Perhaps there is more elsewhere in the memoir.

Pervoskaya’s female comrades wrote much of her, ranging from awed to respectful to glowing. Never anything like what Pinnells describes. This makes me wonder: has he read the women’s memoirs? It would be utterly astounding if he didn’t, yet I wonder how he came away with his incredibly narrow vision of Perovskaya if he had. Barbara Alpern Engel and Clifford N. Rosenthal edited and translated the memoirs of five women of the early movement (Five Sisters: Women Against the Tsar; The memoirs of five young anarchist women of the 1870’s). Four of them worked closely with Perovsakya at various points in her career, and three of them speak of her at length.

Elizaveta Kovalskaia: “A young girl, almost a child, was standing near… Her plain costume set her apart from the others: a modest gray dress with a small white collar that somehow looked clumsy on her, like a schoolgirl’s uniform – you could see that she was totally oblivious to her appearance. The first thing you noticed was her broad, high forehead, which stood out so strongly from her small round face that all the other features were somehow lost in the background. […] [She] replied with extreme restraint, but very stubbornly. Looking closely at her, I saw that below the large forehead were eyelids drawn slightly downward toward her temples; her gray-blue eyes seemed rather evasive, but held a kind of stubborn inflexibility. Her expression was distrustful. When she was silent, her small, childlike mouth was tightly shut, as if she feared saying something superfluous. Her face was deeply thoughtful and serious; her entire figure exuded a monastic asceticism. […] [She] kept asserting that joint circles [with men] were impossible, in view of the fact that men, being more educated, would undoubtedly make it difficult for women to think independently. As the argument flared up…despite my weakness for beauty in general, I found myself more and more attracted to the modestly dressed, ascetic young girl. Many interesting, beautiful, gentle faces passed before my eyes, but again and again my attention would return to the girl in gray. Perhaps it was because her unpretentious clothing was so different from that of the others… Perhaps, too, because this girl resembled one of those stubborn defenders of their faith who carry their cause to the point of self-annihilation – I had been attracted to that type from childhood. […] [T]he girl was Sofia Perovskaia. Perovskaia suggested that I join a small circle of women who wanted to study political economy, and I agreed. As it turned out, only Perovskaia and I came punctually to the sessions. […] Perovskaia would administer sharp reprimands to the latecomers. […] Perovskaia took her studies very seriously. She would stop thoughtfully at each idea, develop it, and raise objections… It was obvious that she was enthralled by intellectual work and enjoyed it for its own sake, not only as a means to an end. […] Perovskaia, too, began coming late to the meetings; she was troubled by something and absent-minded. One time when she was particularly unhappy, she abandoned her usual reserve and told me about her unpleasant personal situation…[of] find[ing] herself in a semi-illegal position. [Not long after the news broke that Perovskaya and a few other women were joining a group with men. Perovskaya offered no explanation.] (213-217)

Olga Liubatovich: “About a week later I had my first, unforgettable meeting with Sofia Perovskaia. […] Around noon, a moderately dressed young woman appeared at the door. Her striking face – round and small, but for the large, childlike forehead – stood out sharply against the background of her black dress, trimmed with a broad white turn-down collar. She radiated youth and life. Perovskaia introduced herself and greed us in the open, direct fashion of an old friend, although she had never met either of us. We clustered around her: obviously, she was pleasantly excited about something. The rapid walk to our apartment had left her breathless, but she immediately began to tell us the story of her escape at the railroad station in Novgorod – a simple story, but it made me tremble… […] The news of Perovskaia’s escape spread quickly through St. Petersburg, and in a few hours Kravchinskii – one of her old comrades from the Chaikovskii circle – hurried over to see her. His attitude toward this child-woman (for that’s how she looked) was striking: it reflected profound respect, a kind of restrained worship, but was altogether consistent with their comradely relations. ‘She’s a remarkable woman,’ he told me later. ‘She’s destined to accomplish great things.’” (153-155) [Liubatovich also describes Perovskaya’s dedication and determination to rescue imprisoned comrades.] “A few days after the Moscow explosion, Sofia Perovskaia appeared at one of the party’s secret apartments in St. Petersburg, where she found Grachevskii, Gesia Gelfman, and me. Perovskaia was generally very reserved, but after Grachevskii left and she found herself alone with us women, the words began to spill out and she emotionally told us the story of the Moscow attempt – all the while standing by the washstand, her hands covered with soap. […] There was a catch in her voice as she spoke, and her face reflected intense suffering; she was shaking, either from a chill produced by her bare wet hands or from a painful feeling of failure and long-suppressed emotion.” (167-168)

Praskovia Ivanovskaia: “For our sakes, one precious exception was made to the prohibition on seeing friends: once a week (on Saturday evenings, as I recall) and in the intervals between printing jobs, we visited Sofia Perovskaia’s apartment. She shared the place with Andrei Zheliabov, and when we stayed late we saw him, too. However, sometimes he didn’t even notice our presence as he walked past Sofia’s open door: he simply went into his room…and dropped onto the bed…as if he had but one invincible desire – to sleep. To us, the visits to Perovskaia were like a refreshing shower. Sofia always gave us a warm, friendly welcome; she acted as if we were the ones with stimulating ideas and news to share, rather than the reverse. In her easy, natural way, she painstakingly helped us to make sense of the complicated muddle of everyday life and the vacillations of public opinion. She told us about the party’s activities among workers, about various circles and organizations, and about the expansion of the revolutionary movement among previously untouched social groups. Perovskaia spoke calmly, without a trace of sentimentality, but there was no hiding the joy that lit up her face and shone in her crinkled, smiling eyes – it was as if she were talking about a child of hers who had recovered from an illness. There were many occasions when Perovskaia reaffirmed for us the value of the work we were doing. During one period in particular, when all of us were depressed, Lilochka began bothering Sofia for a more dangerous party assignment. Lila was younger than the rest of us and the fighting spirit was very strong in her, but it was more a kind of childlike greediness that prompted her request. A shadow fell across Perovskaia’s weary face, as she carefully heard her out, then she walked up to Lila and tenderly stroked her ardent head: ‘Don’t think, Lila,’ she said sadly, ‘that the press is any less necessary and valuable to the party’s work than throwing bombs.’” (123-124)

These women hardly sound bitter about Perovskaya’s leadership style; in fact, they sound trusting of her leadership but, more than this, delighted with her friendship. Secondary sources, too, like Apostles Into Terrorists by Vera Broido, Mothers & Daughters by Barbara Alpern Engel, and Fathers & Daughters by Cathy Porter, give similar assessments of Perovskaya’s character.

Then again, without knowing Pinnells’ sources, it’s hard to find where the lines between fact and fiction fall in his story; I imagine even more so for the average reader who may not have much knowledge of the history.

I do the work of a historian and use the findings of my research to write fiction. So, I have to ask: is it acceptable to misrepresent historical figures in order to…I’m not sure what his aims were. Make his invented female protagonist – or his male one, for that matter – more likable? It didn’t work, incidentally, so I hope that’s not the case.

I’ve spoken at conferences in the past about where history and fiction can come together and coexist. Cohabitate, even. I have described how, paradoxically, the distance afforded by a historical setting can often make it easier for authors and readers alike to digest present affairs by widening their context and highlighting the correlations between past and modern history, arming us with the empathy and insight necessary to comprehend an increasingly complex future. After all, it was E. L. Doctorow who said: “The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.” To which I add, the historical novelist does both. I’ve also described how the expressions “history repeats itself” and “write what you know” are conjoined in the creation of historical fiction.

This last bit is key. “Write what you know” means using your experiences, especially internal, to inform your work. But it also means writing what you know of the history, factually and accurately. Without being informed by what you know in the present. That is a challenge. Writing about terrorism in the 19th century without being informed by a 21st century context is incredibly difficult. As is writing about the concept of “free love” in the late-20th century versus the late-19th. But it has to be done, otherwise the author risks distorting the very period they’re trying to capture.

Maybe it’s different for every writer of historical fiction, although based on talks I’ve been to and interviews I’ve read, it seems pretty much across the board: you do your research as a historian, and then fill in the blanks as a novelist…using the research you gathered as a historian. Otherwise, you risk anachronisms, misinformation, and/or wish-fulfillment. It’s a balance, one that is both obnoxious and challenging, but it does not give authors the right to wantonly alter the character of a real figure, whatever the motivation. If you’re trying to capture the essence of things that happened, then surely it’s your job to record them *as* they happened? Otherwise, you lose all validity. If it hadn’t been so heavy-handed, it might be readable as a means of giving some variation to the movement and depth and shading to Perovskaya’s character…although given her convictions and her actions, and those of her comrades, I’m not sure altering either was necessary. It sort of read as several hundred pages of “I think Sofia Perovskaya was an ugly bitch: here’s why my hot, young female revolutionary who conveniently spends a good portion of the novel nude is way better.”

Alright, mister, put it away. We’re not impressed.

Not sure why Matador willingly published this novel, but I suppose that means there’s hope for anyone. And it’s given me even greater incentive to ensure that my novel is not only written in a way which is engaging and artful, but true to the characters and the eras which inspired it. From the beginning I have considered my primary goal not to be publication but to be ensuring that these women are recognized for their collective accomplishments and remembered for their individual deeds and personalities. My novel is written with this, with them, in mind.

Alas, the same cannot be said of Saturn’s Daughters.

All in all: 0 out of 5.